Addressing the Stigma of “Ex-Convict” Long After a Prison Sentence Ends

This article was originally published by Saskia Keeley on August 23, 2020 in The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs website. Click here to read on www.fletcherforum.org

My work as a photo workshop facilitator in fractured communities began with a rabbi in the West Bank. He suggested I run a program for Israeli and Palestinian women who are neighbors but have no contact. The workshops help to build bridges of empathy and redress belief systems by facilitating cultural awareness and sensitivity. Feeling a need to serve populations similarly deprived of humanity and dignity closer to home, I have focused my work on empowering Americans who are uncertain about their future because of their past. Using the camera as well as therapeutic tools, we shift the lens through which the systems-involved individuals see themselves, and empower them to step into life on their own terms.

The organizations I partner with do inspiring work. Through support, mentoring, determination, empathy, and grit, they help ignite the human spirit, build resilience, and find inner and outer resources. We work with individuals who’ve made the choice to move forward, to do the difficult work needed to improve their situation. We apply trauma-informed practices and address the complex, multifaceted struggles and vulnerabilities of the participants. Workshop participants carry significant stigma and trauma. People of color face a far greater risk of being targeted, profiled, harassed, and incarcerated for minor offenses, and bear additional wounds of systemic racism.

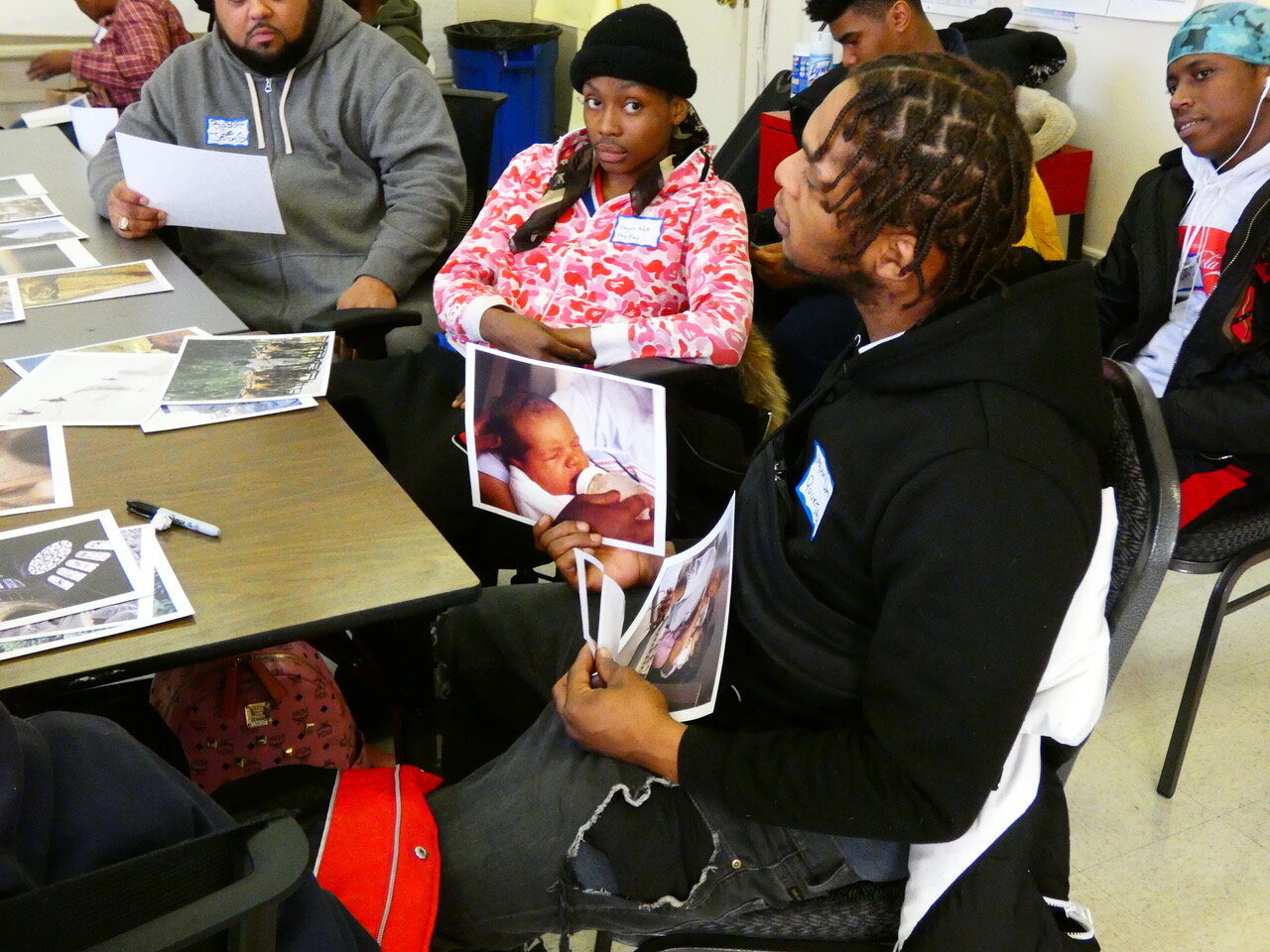

Photographs can be a new language, a way of deeper expression. Trusting that participants have something meaningful to say encourages their creativity. In the act of making photographs, there is introspection. Sharing one’s own illustrations is vulnerable, communal and self-assertive. The camera is a tool to promote storytelling and to enhance understanding. These images catalyze intense conversations during which participants learn to let their guard down and voice their hopes and goals. The commitment is to stay curious and generous and to listen with the same open-mindedness with which we long to be heard. With this premise, we begin to lean into vulnerability, and participants show their authentic selves.

Trusting that participants have something meaningful to say encourages their creativity. In the act of making photographs, there is introspection.

— Saskia Keeley’

A crucial aspect of the workshop is that the participants take the cameras home to photograph their environment with the goal of creating their own personal narratives. Providing the participants with valuable equipment conveys esteem and trust. It is a cathartic moment for many. When Leslie[i] at the Women’s Prison Association realizes that she can take the camera home with her, she cries openly stating, “I can’t believe you would loan us beautiful digital cameras. That you would entrust us with them even though you don’t know us, but you know about our past.” At Friends of Island Academy, Damien exclaims, “I have one question: Are you SURE? I have another question: Are you SURE?” When I smile and nod again, he says, “She is SURE!” Being seen as trustworthy counters the projections that limit them and helps to unlock their potential.

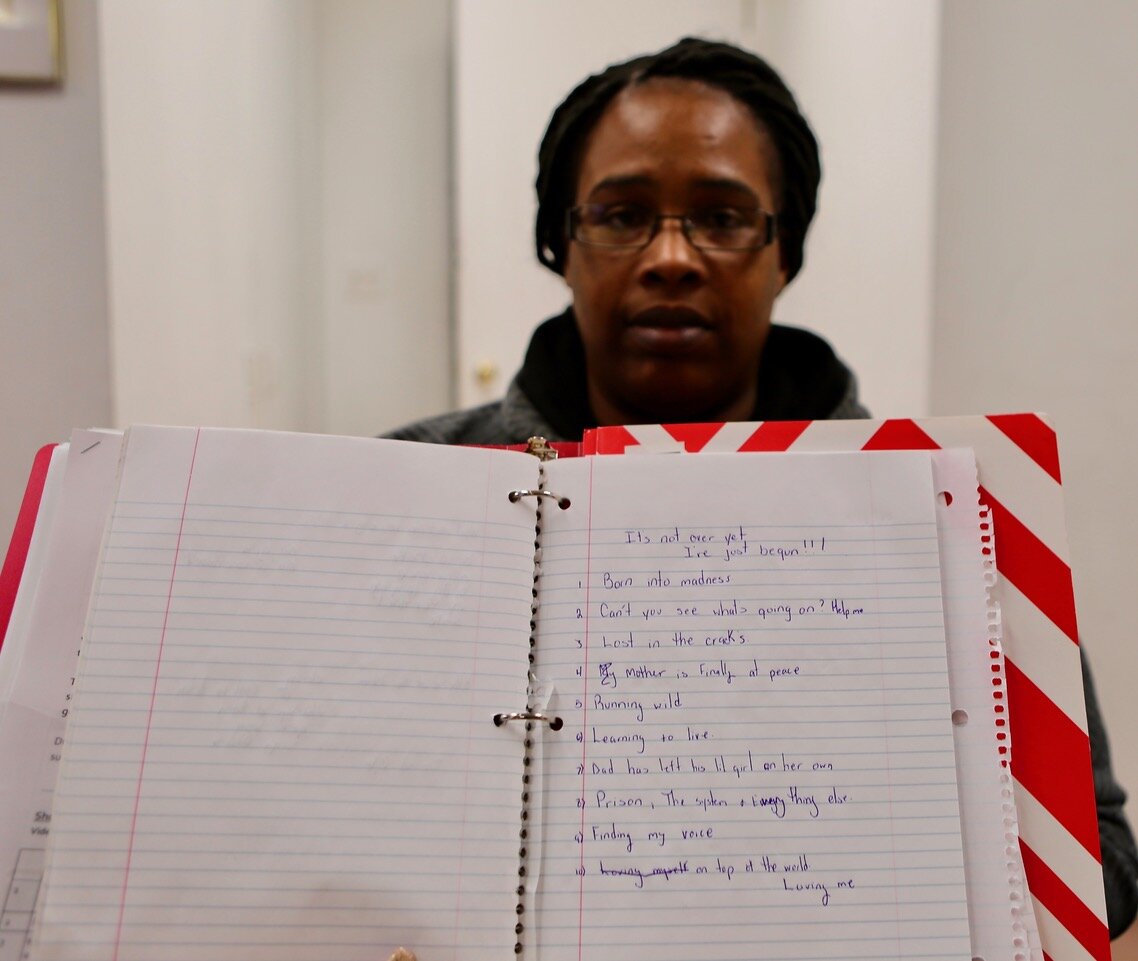

At the Women’s Prison Association, ten women are asked to think of titles for chapters in their life story: one five years in the future and one for their lives as a whole. One title is “If Only I Spoke Up,” another is “The Storm Came and Went.” The chapters include “Born into Madness,” “Can’t You See What Is Going On Here?” and “Prison: The System and How Things Are Done.” These women have never told their stories in this powerful, probing way. This population has been shamed and silenced, judged and marginalized. As the facilitator, my work is to receive the gift of each person’s story, and to bear witness to all its dimensions: the beauty, the pain, the sorrow, and the joy. They each have a unique vision, a way of seeing that is rooted in the particularity of their lives. This shifts the lens through which the world sees them. It empowers them to step into life on their own terms.

At the Friends of Island Academy workshop, a pile of stones sits in the middle of the room. Each stone fits in the palm of a hand. We sit in a circle. Each participant gets up and picks one, then sits down again, holding it. I ask them to think of a time in their lives that involved hardship-to sit with this for a moment. I then ask them to think of the personal quality that they feel helped them come through that difficult time. I want to honor that individual’s unique gift-not revisit the trauma.

At the Friends of Island Academy workshop, a pile of stones sits in the middle of the room. Each stone fits in the palm of a hand. We sit in a circle. Each participant gets up and picks one, then sits down again, holding it. I ask them to think of a time in their lives that involved hardship-to sit with this for a moment. I then ask them to think of the personal quality that they feel helped them come through that difficult time. I want to honor that individual’s unique gift-not revisit the trauma.

Photo courtesy of Joe Chan

Photo courtesy of Joe Chan

Michael says, “when I experience an unexpected and difficult death, all I can do is move forward.” This prompts us to discuss Michael’s resilience and courage. I invite Travis to recognize his own qualities. He falters and can’t seem to find a gift worth mentioning. A week earlier, he’d shared that his 48-year-old mother has advanced dementia due to decades of drug and alcohol abuse. She lives alone and is abusive, paranoid, and unpredictable. Travis can’t be close to her physically or emotionally. So, I mention his mother with dementia and the substance abuse that led to this situation. Can Travis recognize his strength, his adaptability living through this ordeal? Travis looks at me, astounded-saying, “you remember this story? You have an amazing memory!” The lack of very basic attention and care from his own parents and providers seem to have conditioned him to invisibility. For Travis, the experience of having his story heard, being seen and recognized, may be a model for him to cultivate this internal witness in himself. These small, caring moments can be transformational.

Unbeknownst to the participants, a portrait of each person taken in a prior class is printed in a large format and displayed in the last session. Using that portrait, I invite them to claim more of themselves in front of the others as a part of their own internal growth and process. Speaking about their portrait is a step toward acceptance and self-empowerment. This allows us to dare greatly and to have the courage to be vulnerable by searching and mirroring our inner truths.

As long as I live in a world where activist groups are necessary to enlighten society that Black and brown lives matter, I will be on the front lines and in our political systems orchestrating and influencing policies to enact long fought and overdue changes.

— Lorraine

In the conscious process of dismantling collective indoctrination, we need to be fully receptive to the stories of dreams deferred, and the abuse experienced every day by marginalized, at-risk populations. Capturing and amplifying the important stories and personal experience of those deprived of equality and justice are at the core of our mission. Time and time again, I have borne witness to the drive of remarkable trailblazers such as Lorraine, a systems-involved participant now finishing her Masters degree. She writes, “as long as I live in a world where activist groups are necessary to enlighten society that Black and brown lives matter, I will be on the front lines and in our political systems orchestrating and influencing policies to enact long fought and overdue changes.”

The heartening outcome of the workshop is individuals who are able to tell their stories with acceptance and embrace their future with purpose, to find their individual voice or a collective one. I am inspired by their wisdom and focus. Proximity to the injustices in their lives gives them expert insight into the solutions to end them, and an opportunity to improve policies toward a socially inclusive environment.

[i] All names have been changed for privacy