Creating Brighter Lives for Syrian Refugee Children

I spent ten days documenting the NGO Taghyeer / We Love Reading initiative in Jordan. During my time on the ground, I met many hardworking and inspiring people from the We Love Reading [WLR} community - from support staff and coordinators to women (and a few men) training to become reading ambassadors.

WLR ambassadors foster a love for reading in young children living in indigenous communities and Syrian refugee camps across Jordan, with ambitions to spread across the Middle East and around the world.

Here is a short video I made introducing the work being done by We Love Reading:

Each and every one of those interactions was meaningful and poignant, a testimony to the great mission of We Love Reading. Below, I chronicle my two days in the Azraq Camp.

Published in The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs: Photojournalism: Creating Brighter Lives for Syrian Refugee Children. Click here to read on fletcherforum.org

"We read for ourselves, our children, our community, our future."

The instant I connected with Dr. Rana Dajani, the founder of the NGO Taghyeer / We Love Reading, I knew I wanted to collaborate with her. A Jordanian molecular biologist, Dr. Rana is an Associate Professor at Hashemite University in Jordan. After spending 5 years abroad, witnessing the easy access to books and libraries, Dr. Rana came back to her country with a heightened awareness that instilling the love of reading wasn’t a high priority for most cultures in the Middle-East. Through personal experience, she saw the positive impact literature can have and how children’s aspirations can be raised when they see the world through someone else’s eyes. So Dr. Rana set up her very first library in a local mosque more than ten years ago.

Dr. Rana Dajani

The concept is simple: to foster the love of reading among children.

Make reading enjoyable and it will provide hope and an ability to dream.

Reading aloud regularly to children aged 4 to 10 helps them to discover their inner potential. It seems so basic, this notion could easily be dismissed. But the stories Dr. Rana shared about what We Love Reading offers in Jordanian neighborhoods and in Syrian refugee camps were truly inspiring. As with many communities limited in resources, proper education is scarce in camps. In addition to providing literacy and an appreciation of written words, reading is also a tool for increasing well-being, promoting resilience and alleviating mental stress. It also helps to create a sense of community.

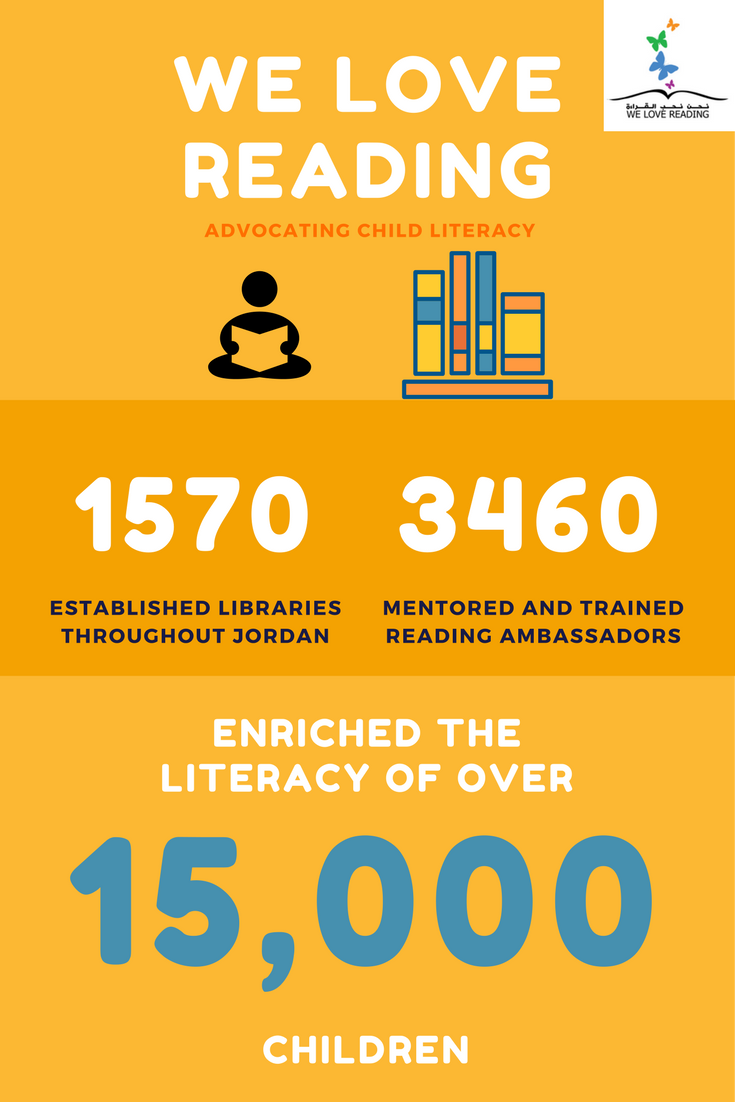

The We Love Reading (WLR) program advocates for child literacy. To date, they have mentored and trained 3460 people - mostly women - in techniques of storytelling. The program empowers the adults who wish to better their own lives and the lives of those around them. These efforts have led to the establishment of 1570 libraries throughout Jordan, enriching the literacy of over 15,000 children.

Beginning with weekly reading sessions in a local mosque in 2006, the program has since grown into an established NGO with libraries - meaning a place where the trained volunteers hold weekly sessions – in 33 countries. Based in Amman with a staff of 30 employees, WLR’s mission is to expand the program as far as possible, and to monitor and evaluate every library that has opened since its implementation.

The ultimate goal is to reach every child in every neighborhood in the world by 2020.

The opportunity I had to witness this truly transformative and purpose-filled program was beyond inspiring. In all the Jordanian communities we travelled to—from Ma’an in the Southern part, to Irbid in the North, to Mafrak in the East—I listened to true storytellers reading to groups of rapt children.

Reading sessions in Jordanian communities

Those storytellers, called ambassadors, are volunteers who have finished the two-day training to become WLR readers. The groups of children I observed ranged in size from a dozen to more than 40. The ambassadors all shared their enthusiasm about the program and what it offers the children: a chance to dream, grow, and learn.

![]()

They also spoke about what they had gained by becoming committed participants. Majed Mohammad Qasham, an ambassador, said,

The opportunity to spread joy and bring hope is precious, but it’s especially meaningful in a context often devoid of occupation and purpose. The program is transforming cultures from the ground up and empowering individual change-makers who wish to make a real difference.

Possibly the most moving interactions happened during my two-day visit to the Azraq Syrian refugee camp. I accompanied two WLR coordinators—Ms. Sarah Shahin and Ms. Sukayna Anbtawi—to hear the latest group of ambassadors reading to the young in their communities. I was granted official permission to enter only three days prior, as camps are tightly restricted.

Azraq Camp opened its doors in 2014. It now has 35,000 refugees, with space for thousands more. To get to the camp, one drives an hour and a half, about 70 miles east from Amman. Looking out the window, the scenery is one of barren desert for most of the ride. The striking landscape, with a whiteness of light and sand that stretches as far as the eye can see, gives off an eerie feeling of remoteness. But even this doesn’t prepare the newcomer for the desolate vision of Azraq. In the hot desert landscape, far from any urban area, the camp suddenly comes into sight. From a distance, one can see endless rows of white steel “caravans”: hundreds upon hundreds of shelters, each family assigned to one. While clearly a well-planned and thoughtfully designed camp, enclosed in fences and barbed wire, it looks like a military camp.

Those storytellers, called ambassadors, are volunteers who have finished the two-day training to become WLR readers. The groups of children I observed ranged in size from a dozen to more than 40. The ambassadors all shared their enthusiasm about the program and what it offers the children: a chance to dream, grow, and learn.

Majed Mohammad Qasham

They also spoke about what they had gained by becoming committed participants. Majed Mohammad Qasham, an ambassador, said,

“Even if I vanish now, it’s all right, because the most important thing is that I brought help and support for people in need.”

The opportunity to spread joy and bring hope is precious, but it’s especially meaningful in a context often devoid of occupation and purpose. The program is transforming cultures from the ground up and empowering individual change-makers who wish to make a real difference.

Possibly the most moving interactions happened during my two-day visit to the Azraq Syrian refugee camp. I accompanied two WLR coordinators—Ms. Sarah Shahin and Ms. Sukayna Anbtawi—to hear the latest group of ambassadors reading to the young in their communities. I was granted official permission to enter only three days prior, as camps are tightly restricted.

Azraq Camp opened its doors in 2014. It now has 35,000 refugees, with space for thousands more. To get to the camp, one drives an hour and a half, about 70 miles east from Amman. Looking out the window, the scenery is one of barren desert for most of the ride. The striking landscape, with a whiteness of light and sand that stretches as far as the eye can see, gives off an eerie feeling of remoteness. But even this doesn’t prepare the newcomer for the desolate vision of Azraq. In the hot desert landscape, far from any urban area, the camp suddenly comes into sight. From a distance, one can see endless rows of white steel “caravans”: hundreds upon hundreds of shelters, each family assigned to one. While clearly a well-planned and thoughtfully designed camp, enclosed in fences and barbed wire, it looks like a military camp.

Azraq Camp

Only with governmental permission can one get an entry permit, pass the strict security gate check, and gain access to the “villages” that constitute the camp. All visitors must be accompanied by a camp official, but there was even more security around our arranged appointments.

As I am a photographer, and because this was mentioned in my paperwork, we were followed by a policeman throughout our two-day visit. I learned early on that there were restrictions as to what I was allowed to photograph. During the first day, the policeman asked to review photos on my camera’s LCD screen and made me erase all images taken up until then. The stated reason was to protect the displaced people but my perception was that they closely monitor the images and the reports coming out of the camp.

It is clear that the management of the camp is strictly controlled not just for visitors but, more critically, for the refugees inside, which limits mobility, and decreases opportunities for employment both inside and outside the camp. It is challenging for residents to have any control over decisions as crucial as making a living, let alone finding ways to fill their days with meaningful activities.

There is a sense of temporariness to Azraq. One has the feeling that time is suspended. It is eerily quiet, with none of the life and noises we are used to in any typical large community: cars, music, the buzzing of activities or children playing. Most people seem to remain indoors. While it’s evident that the camp is not intended to be permanent, there is no avoiding the disquieting feeling that without a political solution, the suffering of Syrian refugees will continue and camps such as Azraq will continue to be more than just temporary shelters.

Eerily quiet streets

The Jordanian communities that host refugees feel the impact of providing for them. Mohammad Momani, Minister of State for Media Affairs, talks about “standing on high moral ground when it comes to aiding refugees,” but stresses the crucial importance of the international community in helping to shoulder responsibility in this crisis.

Many local and international organizations collaborate—such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), UNICEF, and the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), INJAZ, and WLR—providing large financial and technical support to the camps in Jordan, supplying basic needs such as shelter, sanitation, food, medical treatment, and education. But the sheer number of civilians in need of aid presents challenges to relief groups on the ground.

At this stage, there are 1.3 million Syrian refugees in Jordan, representing almost 20 percent of the country’s population.

This is all part of what I experienced when I spent one day in Village 2 and the next in Village 6. I saw the noble efforts of international organizations and the benefits that come from their generous support, I witnessed dedicated local workers on the ground who make the refugees’ lives more bearable. But families coping with the stresses of life far from their Syrian homes can only adapt so much in a confined, highly secured and enclosed area. They struggle to provide for their families and to access essential services – including education for their children.

The initial worry was that a WLR initiative would be hard to get off the ground in a camp where refugees would be more concerned with satisfying basic needs such as food and shelter. Many children are not even sent to school, as there is little faith in what education can provide while living in a challenging setting and in a traumatized state.

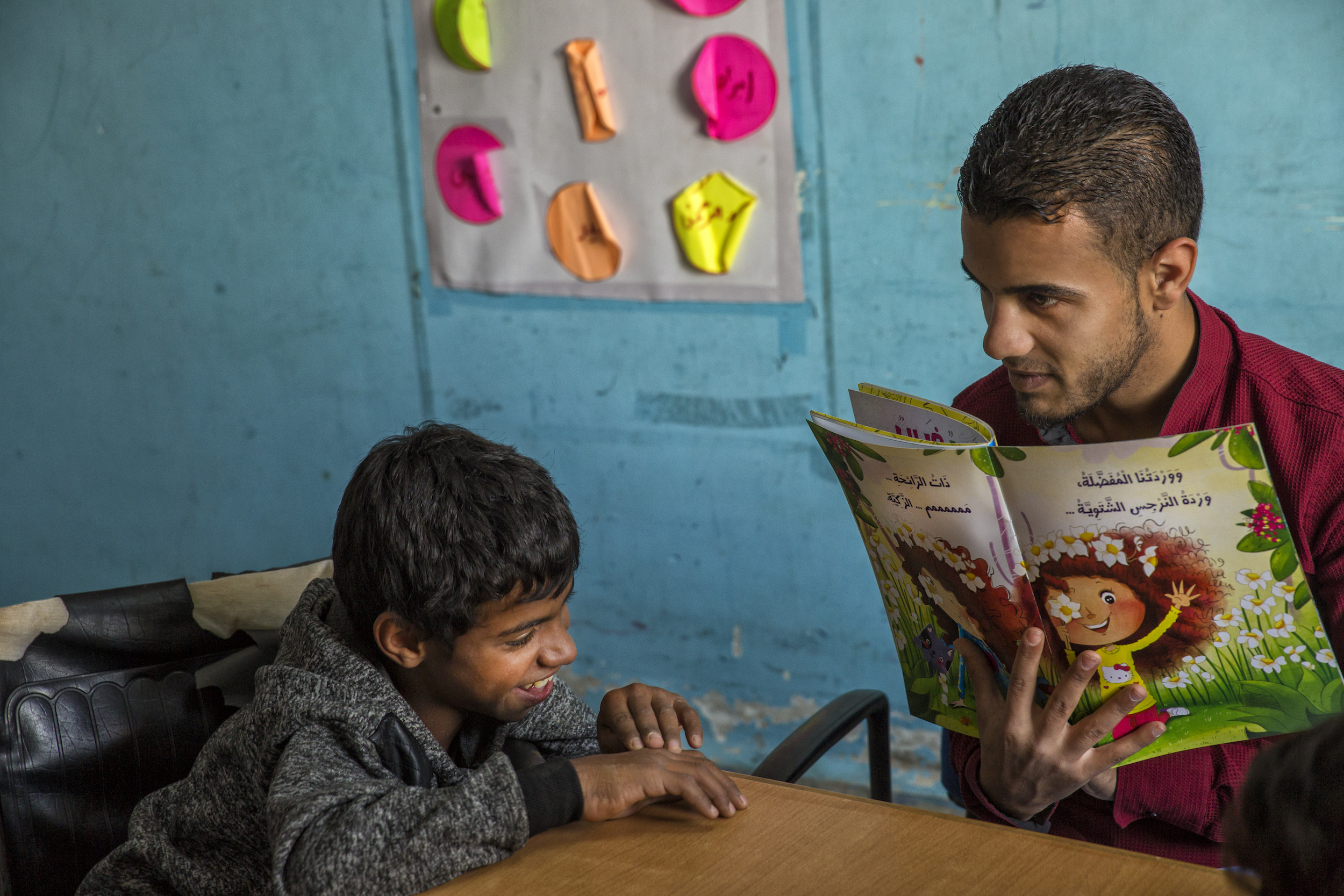

Against all odds, WLR held two training sessions, the first in 2016 and the second, just a couple of months ago. They were both met with great success. More than 30 trainees became reading ambassadors and they all opened libraries: finding places such as their home-caravan, the school center or the mosque where they can hold reading sessions on a weekly basis. Some gather children even more regularly. Ismail Yasin Al Thaher, an ambassador who reads every afternoon in Village 2, says he has counted 150 children who come at different times to hear his stories.

Our two days in Azraq were planned so that I could document the reading sessions given by some of the newly trained volunteers, and so that Sarah and Sukayna could do the follow-up that takes place after every training program.

In the camp, storytelling occurs either in a “class” caravan or outside in an open-air area surrounded by caravans, making it an enclosed area.

Ismail Yasin Al Thaher in Village 2

There is no doubt that I created a distraction as a tall, foreign-looking visitor equipped with photography gear. The children excitedly looked my way as I was setting up my equipment. The reading ambassadors knew of my visit and welcomed me warmly. They are proud of their storytelling skills, which attract dozens of children to come and listen to their every word, and provide an opportunity to step away from the grim daily reality.

They are also immensely grateful to have the opportunity to use literacy to bring meaning to the lives of children, as well as their own. Her own love of literature compelled one ambassador to the project, in order to help “build a generation of readers, an educated and civilized generation.”

I was deeply impressed by the way the sessions are structured and planned out, how they have become such an important part of any day’s activities. Many of the books are read over and over, but the children still love hearing about Jude or Amal or Samir, the protagonists in some of the stories. They interject and laugh, they wait eagerly for specific moments in the narrative.

They are also immensely grateful to have the opportunity to use literacy to bring meaning to the lives of children, as well as their own. Her own love of literature compelled one ambassador to the project, in order to help “build a generation of readers, an educated and civilized generation.”

I was deeply impressed by the way the sessions are structured and planned out, how they have become such an important part of any day’s activities. Many of the books are read over and over, but the children still love hearing about Jude or Amal or Samir, the protagonists in some of the stories. They interject and laugh, they wait eagerly for specific moments in the narrative.

A new book that talks about the refugees’ plight

This visit to Azraq was all the more special: two new books were just published and printed by WLR and we brought them with us. They depict the refugees’ plight. These beautifully illustrated stories show Syrian families leading happy lives in their country. Then the war comes and they need to flee to survive. The bright and colorful pictures turn dark and grey, capturing the fear and anguish. The palette remains somber with the arrival in refugee camps and the hardship of adjusting to unfamiliar, restricted dwellings. The end of the story is hopeful, speaking of new beginnings and fresh possibilities in an environment that at first felt foreign and distant. Children paid close attention, a sort of quiet observation, to this new story. I sensed it is a narrative they know all too well.

For the ambassadors, reading aloud becomes an essential medium for communication between generations, a way to heal trauma inflicted by war.

When I spoke to them individually, with the help of a translator, they all mentioned the sense of purpose those reading sessions have provided them, a gift beyond anything they hoped to get from the experience. Najla Abdulla Sharah says,

She sees this as an opportunity “to create a cultured, civilized, educated generation, literally a building block for the new generation.”

“I wept profusely the day I participated in WLR.”

She sees this as an opportunity “to create a cultured, civilized, educated generation, literally a building block for the new generation.”

Najla Abdulla Sharah

The second day was even more revealing. We listened to the first five ambassadors reading, each to their own group of children. These sessions were all given within the physical structure of the school and the activity center for Village 6, a larger structure than Village 2.

Reading session on the soccer field with Village 6 beyond the blue fencing

Over and over, I experienced the same dedication and passion coming from the volunteers and the same earnest attention from the children, as they leaned forward to see the illustrations of the book, to be a full participant in the storytelling.

Mosque

Our last two sessions were in the Village 6 mosque.

This place of worship is an especially large caravan where our last two ambassadors read. The mosque is a half-mile away from the school center, and our assigned policeman relaxed the strict restrictions. He allowed us to walk, giving us the opportunity to go by home dwellings and spend more time with refugees.

Walking with children in Village 6

Curious children followed us as the women explained more about the structure of their communities and how to subsist when so little is available. The rainy season is about to begin. The dry soil will turn into mud and the dusty air into a dampness that will permeate their homes. Winters are harsh and gas supplies given to families aren’t distributed often enough to keep the shelters warm.

With this unique opportunity to experience all that was around us, we ended up rushing to the last two reading sessions in the mosque. The ambassadors and the small, endearing group of girls gathered quickly and efficiently.

Inside the main room in the mosque

Being behind schedule, we moved from the main room to a smaller one when it was time for prayers, and men came in for the afternoon gathering. One of the two ambassadors used to be an English teacher in Syria and it was wonderful, as well as heart-rending, to hear her account first-hand. Some of the vibrancy of such exchanges is lost waiting for translation by a third party. The uniform account from all was how much this program has provided in terms of building hope, joy, imagination, and in promoting culture and education. All of the ambassadors commended Dr. Rana Dajani and her NGO for a vision that has been life-transforming and salutary.

On the ride back to Amman, it was too early to sort through the overwhelming and conflicting feelings those two days had prompted. Witnessing the level of adversity, the forced confinement, the extreme limitations brought about a concrete reality beyond anything imaginable. Even with the stark accounts and images on the news, the lives of refugees remain abstract until seen first-hand.

In the greatest humanitarian tragedy of the 21st century, hundreds of thousands are facing extreme hardships with no solution or end in sight. But the Syrian war has also given humanity a chance to act. During my two days in Azraq Camp, I witnessed acts of human compassion countless times: in the kindness of teachers, in the aid and assistance of relief workers, in the dignity that can be restored through programs such as We Love Reading, in the uncompromising commitment and dedication of reading ambassadors. It is to those ambassadors—exemplifying virtue, spreading light, being moral beacons amid the darkness of a tragic war—that I dedicate this article.

If you enjoyed this article and wish to help please donate here, or purchase the photography above. All proceeds go straight towards funding more humanitarian work that I conduct personally.